Receipts: Booker T. Washington’s “slave” food memories

By Fresh & Fried Hard

This article was originally published by Fresh & Fried Hard. You can subscribe to read more of their content on Substack.

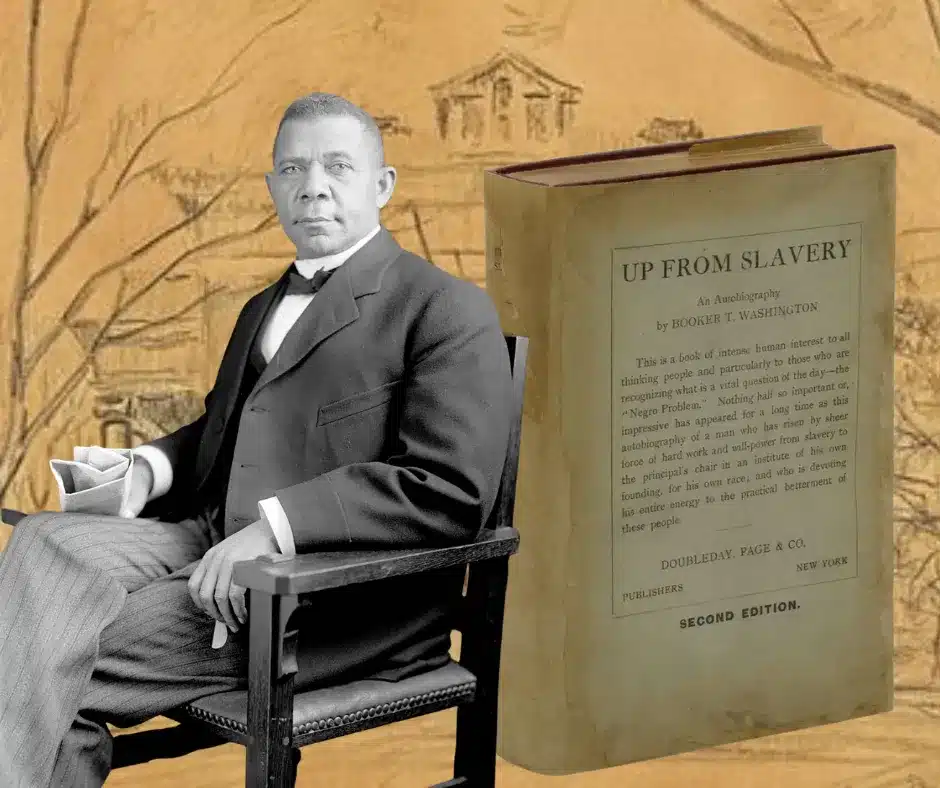

There’s something insightful about first-person accounts, in “Up from Slavery” Booker T. Washington allows us to see how his earliest food memories influenced his lifestyle and style of leadership

Booker T. Washington was an intriguing personality. His family line is rooted in the Appalachian sub-region of SW Virginia and West Virginia. He married Olivia Davidson, his second wife in Athens, OH in SE Ohio. And Tuskegee is located in a sub-region of Appalachia in Alabama.

Tuskegee Institute was developed on his self-determination principles and he made certain that the students were fully invested in their own education at the institute. They literally made the bricks, constructed buildings, worked the land to grow the food they ate and sold… They carried their own weight. That was one of his chief selling points to white donors, who donated heavily to Tuskegee. It is safe to say Washington argued that it was better to labor at an institution made for Black folk than to labor at an institution that wouldn’t admit Black folk as students.

Some of the world’s leading scholars in the sciences (George Washington Carver) and the arts and humanities either worked at Tuskegee or were alumni. There were also the entrepreneurs who graduated from Tuskegee; people who embodied Washington’s belief that Black people should own businesses.

In many ways, he used his own life as a blueprint to establish Tuskegee.

In his autobiography Up from Slavery he offers details about his mother Jane Ferguson. Born into slavery, Jane Ferguson worked as a cook on the plantation of James Burroughs. After emancipation, she worked as a cook for the Ruffner family in Malden, West Virginia until her untimely death in 1874.

While Jane Ferguson’s claim-to-fame is Booker T. Washington, she was a pioneer in her own right. After moving to Malden, she became the town’s first Black homeowner despite receiving threats from the Ku Klux Klan. Through her church, African Zion Baptist Church, she worked with members of the congregation to assist others transitioning from enslavement to freedom.

In Chapter 1 of his book, Washington writes, “I cannot remember a single instance during my childhood or early boyhood when our entire family sat down to the table together, and God’s blessing was asked, and the family ate a meal in a civilized manner. On the plantation in Virginia, and even later, meals were gotten by the children very much as dumb animals get theirs. It was a piece of bread here and a scrap of meat there. It was a cup of milk at one time and some potatoes at another. Sometimes a portion of our family would eat out of the skillet or pot, while some one else would eat from a tin plate held on the knees, and often using nothing but the hands with which to hold the food. When I had grown to sufficient size, I was required to go to the “big house” at meal-times to fan the flies from the table by means of a large set of paper fans operated by a pulley.”

Washington emphasizes that as a family unit, they didn’t experience a traditional family dinner like the people his mother served. He also lets the reader know that while his mother was the plantation cook, food was sparse for him and his siblings.

He continues, “Of course as the war was prolonged the white people, in many cases, often found it difficult to secure food for themselves. I think the slaves felt the deprivation less than the whites, because the usual diet for the slaves was corn bread and pork, and these could be raised on the plantation; but coffee, tea, sugar, and other articles which the whites had been accustomed to use could not be raised on the plantation, and the conditions brought about by the war frequently made it impossible to secure these things. The whites were often in great straits. Parched corn was used for coffee, and a kind of black molasses was used instead of sugar. Many times nothing was used to sweeten the so-called tea and coffee.”

Tuskegee under Washington’s leadership was a leader in an agricultural movement that included a fully-functioning farm on the campus, food and agriculture programs that taught entrepreneurship, and a science program guided by George Washington Carver. As brilliant as his foresight was, it is not hard to imagine how his hindsight also influenced the college’s mission.

As a leader, Booker T. Washington received invitations to eat at the finest of restaurants and dining establishments, including the White House. Whatever he thought was lacking in his days as an enslaved child, he had an opportunity to repair as an adult. Booker T’s ‘slave food’ memories turned into family dinners, more than enough to eat, and a choice of the finest foods. And he made it his business to ensure that others enjoyed the same privileges through his work at Tuskegee.

References:

[Joseph McGill of The Slave Dwelling Project provides his insights on Jane Ferguson’s life as a plantation (more large farm) cook: Booker Taliaferro Washington]

[Sketch in featured image: Aaron Douglas Charcoal Drawing, Tuskegee Institute.]

If you appreciate BBG's work, please support us with a contribution of whatever you can afford.

Support our stories