The Hillbilly and Bricktop: How A Quirky West Virginia Newspaper Kept An International Star Connected to Home

A Note on This Journey:

I’ve been working on a book about Bricktop for years now — collecting clippings, following leads through archives, letting her story simmer and steep like good sassafras tea. In my first essay, “Bricktop’s Charleston: What The Appalachian Cabaret Queen Taught Me About Home,” I confessed that part of what’s kept me circling this story is its sheer magnitude — like her name, Ada Beatrice Queen Victoria Louise Virginia Smith, known as Bricktop, is big!

My goal is to release an essay every two weeks on my free Substack — I hope you will join and support this journey.

Thank you for your support.

~ cg

Claiming Our Names: A Prayer, A Pun, A Declaration

In 1956, Jim Comstock launched The West Virginia Hillbilly, a newspaper from his hometown of Richwood, turning what outsiders saw as a joke into a declaration of Appalachian pride in its name, as does Black By God. Both names are acts of claiming — Hillbilly then, Black By God now — and BY GOD YOU can be whatever West Virginia you want to be too.

We’ll bring the best from BBG right to your inbox. You can easily unsubscribe at any time.

Sign Up for our Newsletters!

For nearly three decades, his “weakly” paper — as Comstock himself called it — became a lifeline connecting West Virginians across the globe to their mountain roots. Through these pages, I discovered not just Bricktop’s connection to home, but my own connection to a lineage of publishers who understood that keeping our diaspora tethered to West Virginia is essential.

I’ve been collecting Hillbilly clippings on Bricktop for years now — digging through archives, following leads. The West Virginia History and Archives has been especially helpful, as have the Greenbrier Historical Society archives in Lewisburg. Comstock’s coverage of Bricktop has shown me something essential about the work we do at Black By God: we’re not just reporting the news. We’re creating a historical record and keeping our diaspora home.

The Publisher Who Transformed a Hillbilly Slur Into Pride

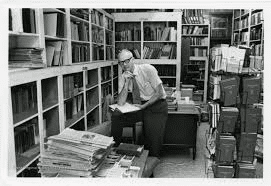

Born in Richwood in 1911, Comstock was an unlikely newspaperman who understood the power of claiming your identity before anyone else could define it. A former teacher at Richwood High School, he ran The Hillbilly with a self-deprecating sense of humor, calling it “a newspaper for people who can’t read, edited by an editor who can’t write.”

When he named his publication The West Virginia Hillbilly, he transformed a slur into a badge of pride. Writer Matthew Neill Null describes in The Paris Review how The Hillbilly was more than just a paper — it was an art project, a platform for historic preservation, and an exploration of the West Virginian spirit. At its peak, circulation reached 30,000, with subscribers across the country and overseas.

Comstock was theatrical. In his most infamous stunt, he added ramp oil to the printing ink one spring. Warehouses full of mailmen gagged. The postmaster general sent a stern rebuke. Comstock’s response? “Now we’re the only newspaper under orders from the federal government not to smell bad.”

But beneath the pranks lay a serious purpose. You have to have moral courage to write anything meaningful in a small-town paper, and Comstock had it. He pushed to save Pearl S. Buck’s homeplace, organized nature walks to Cranberry Glades, and fought to save Richwood’s clothespin factory.

Most importantly, Comstock gave voice to those West Virginians who had “donned shoes,” as he would say — who had gone to college and become country lawyers and newspaper writers, dentists and nurses, bureaucrats, mine engineers, and international legends like Bricktop.

A West Virginia Girl Who Became Paris Society

Known as Bricktop, Ada Beatrice Queen Victoria Louise Virginia Smith was born in Alderson, West Virginia, a red-haired, freckled girl who left at five years old and grew up to become one of the most influential figures in international nightlife and jazz culture.

For over four decades, she ran legendary clubs across three continents — Paris, Mexico City, Rome — mentoring generations of performers, teaching the Charleston to European royalty, and creating spaces where jazz became the soundtrack of the elite. She advised the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, championed Josephine Baker, collaborated with Cole Porter and Duke Ellington, and became a legend of the international cafe society scene. At Bricktop’s on the Rue Pigalle, European royalty danced alongside American jazz legends.

But she never stopped being from West “by God” Virginia.

As The Hillbilly claimed, she said it like a benediction, as if saying West by the grace of God, and that it is.

Keeping the West Virginia Diaspora Home

Publisher Comstock recognized his role as a keeper of West Virginia’s diaspora stories. He wrote about Bricktop, sent reporters to catch her shows in Paris, and made sure her name found its way into The Hillbilly and back to West Virginia.

He proved that regional newspapers could be both fiercely local and internationally relevant, that pride in mountain identity was powerful. He fought back against a West Virginia narrative with pride, humor, and meticulous documentation of mountain genius, and Bricktop was part of that dissent.

Bricktop embodied and defied: “Hillbilly.”

As publisher of Black By God, I see myself in the Hillbilly’s lineage — a small publisher and local performer keeping track of our diaspora, making sure West Virginians know who we are and what we’ve contributed to the world.

Even though Bricktop wouldn’t have approved of our name — she didn’t like the word Black — but maybe that’s just the point. A name is everything, and she claimed “100% American Negro with an Irish temper inherited” with pride, the same way Comstock claimed “Hillbilly,” the same way I claim “Black By God.” Different words, different eras, same defiance, same love, same insistence on defining ourselves.

Through The Hillbilly’s pages, Comstock allowed West Virginia to claim Bricktop as its own. While she entertained European nobility, back home in Richwood, Comstock was making sure West Virginians knew: Bricktop is ours.

Of all her international clippings, I imagine The Hillbilly was one she treasured and showed friends.

In a March 24, 1973 interview with The Hillbilly, she tells how when her publisher wanted her to write tell-all books full of scandal, Bricktop asked: “How could I ever face the people of West Virginia if I stooped to write scandals?”

West Virginia was her conscience.

The fact that the people of West Virginia, a place she left at five years old but somehow for some reason always claimed as her roots — West by God Virginia — and returned only in the pages of the Hillbilly and a few Charleston Gazette articles, could hold such sway over her choices says everything.

And West Virginia is my conscience, too. This book has to be good, not just for Bricktop but because it’s a West Virginia story.

The Hillbilly told me Bricktop wanted a BIG party in West Virginia. She hoped Governor Arch Moore would invite her to the mansion for Thanksgiving, or that she could plan a gala. Neither happened.

I feel like it’s my duty to throw Bricktop that party one day — I’m imagining in Doris Fields aka Lady D, Bob Thompson, Jordan Dyer, Timmy Coutts, Mark Price, The Appalachian Soul Man, Gardenn, all the musicians, poets, that live in her legacy, along with the specific details she wanted. She told The Hillbilly her details down to the colors gold and red, and that she wanted it to raise money for orphaned children, a cause she dedicated her life to.

But here is the encore. That may not be her only wish that we are left to fulfill.

Bringing Bricktop Home: The Rumored Final Wish

Rumors persist about Bricktop’s final wish. Supposedly, she told Jim Comstock she wanted to be buried back in West Virginia — in Alderson, among her people. It makes sense, and it doesn’t, that she would trust this Hillbilly publisher from home with such a detail.

The story goes that, before his death, Comstock carried this promise to a friend (my grandfather’s friend, too), the Earl of Elkview, but neither eccentric gentleman ever fulfilled the covenant. This may be true, or it may just be a play that was performed during FestivALL featuring the great Shayla Leftridge.

My journalistic skills have failed me here — so I’m asking readers to help me find the details, maybe the play’s script, anything.

Bricktop’s body remains in NYC. But I’ve been to her father, mother, and sister’s graves on a beautiful mountain top in Alderson. It seems like Bricktop should be there, that she should finally come home.

Does anyone remember this play? Do you know who wrote it? If you have any information, please reach out to crystal@blackbygod.com.

Whether this story is a historical fact or mountain folklore, it represents the deep belief that even those who achieve global success carry an eternal connection to home.

And now, it’s my turn to carry it forward — one essay, one archive dive, one story at a time, bringing Bricktop home.

Sign up for Crystal’s substack here!

If you appreciate BBG's work, please support us with a contribution of whatever you can afford.

Support our stories