10,000 hours to change your life – 100 Days In Appalachia Newsletter #3

By: Monstalung

This article was originally published by 100 Days in Appalachia, a nonprofit, collaborative newsroom telling the complex stories of the region that deserve to be heard. Sign up for their weekly newsletter here.

This is part of 100 Days in Appalachia‘s Creators & Innovators Newsletters.

Last week I interviewed about the new Appalachian hip-hop compilation album “No Options,” released on June Appal Recordings.

I have three featured songs on the album. The interviewer asked me about being a new songwriter, after doing years of music production, and inquired about the first song I ever wrote. My response to the latter question was “Like Dis,” which is one of the songs on the “No Options” album.

However, I corrected my answer after thinking about it. The song “Coexist,” the first song of my latest album “An Appalachian Hip Hop Story Pt. 1,” is also the first song I wrote for myself in over 30 years of making music.

As I reflected, I know there are a few factors why I never really started writing lyrics until recently. The most important reason being my commitment to mastering my craft of beat-making. Second to that is my philosophy of how to master a craft.

From a very young age, my favorite parts of classic martial arts film plots are when the young martial arts student seeks a master to train them, and the master explains to them that the training will be hard and long. Then the eager student trains hard for years – working on their skills until the master comes and talks to his now adult student, telling them they are ready, and they must use their skill to help bring peace to the world.

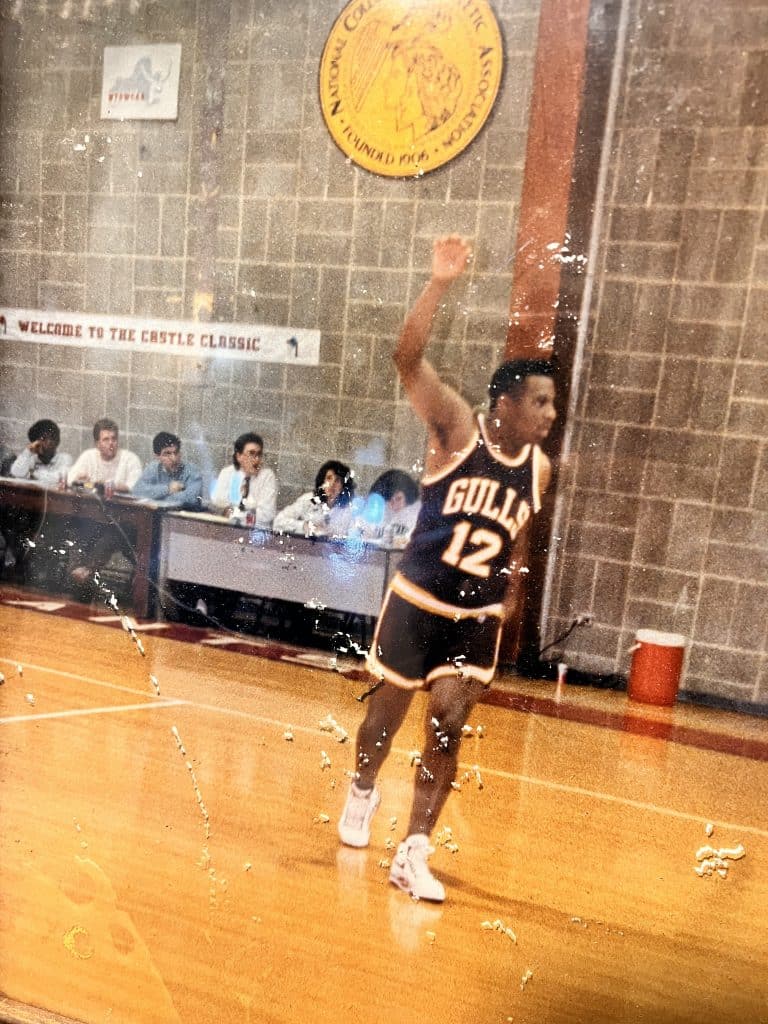

When I was younger my mother would unplug our TV, put it in the closet, and make me and my brother Gandhi read books. Some of the books I always gravitated to were athletic biographies with their common theme of work ethic which could give an advantage to those with talent or level the playing field for those not as talented.

In basketball training, the more shots you shoot, the better of a shooter you become. Reading that college and professional basketball players that I admired would shoot 1000 jump shots a day connected with me. However, it was the theory on free throw shooting that stuck with me more. Specifically, the goal to shoot the same way every time, every detail – that same ritual, to create muscle memory.

The definition of muscle memory is the ability to repeat a specific muscular movement with approved efficiency and accuracy through practice and repetition.

The next example that stuck with me was when I ran hurdles on our track team at Morgantown High. I was taught as a hurdler you want to create a rhythm of 3 steps between hurdles and breathing.

Every time I ran hurdles, I was looking for the rhythm my legs would make: ten steps to the first hurdle, then three steps between each hurdle. My breathing went over the actual hurdle, so in my head I was listening to my steps and breathing, trying to keep them in sync, not letting it get off beat. In theory, if mastered right I should be able to run the hurdles blindfolded, all off muscle memory and rhythm, but I never tried it.

Because I committed myself to the art of repetition and had a strong work ethic in athletics at a young age, I applied those same principles to my music. I knew the more beats and songs I created the better they would get. When I mentored and developed artists, I would tell them not to focus on these early songs they write. Some will be really dope, but it’s song number 50 you want to hear. By then work ethic and repetition should have helped the artist grow.

Also, when developing vocal artists, I made them memorize their lyrics. They were not allowed to read their lyrics when recording. There were several times I refused to continue a studio recording session with an artist because they wanted to read their rhyme off the paper or their phone.

I created this standard because I truly believe reading during recording takes away from the delivery of the vocal because part of your brain has to focus on reading, but when it’s memorized you can play around more with vocal delivery. I also did it just to try to establish a work ethic in the artist to the point that they value it like I do. Not sure if that worked or not with other artists, but I know it works for me.

At the peak of our independent hip-hop label, 90% of my artists were working full-time jobs, getting off work, coming to the studio, and working on music from 6 pm to 4 am, go home take a power nap and be at work by 8 am. And on the weekend, we did shows, manufactured, packaged, and sold CDs on the streets. Our motto back then was: We will sleep when we’re dead.

In the song “Spaceships” by Kanye West, he said he did five beats a day for three summers. I made a minimum of three beats a day from 1995 to 2005, and that repetition only slowed down because I needed to focus on the business of the running an independent record label, including artist management.

Trust me, all those beats were not good, but it was always about getting the reps in. I knew the beat I just made might not be good, but the repetition would undoubtedly influence a future dope beat. That has always been my mindset, and still is.

Not sure when I was introduced to Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000-hour rule, where to become an expert, you need 10,000 hours of practice in that field. But to someone like me who values work ethic and repetition, it made perfect sense. I later found out he used the music group The Beatles as an example from when they lived in Hamburg, Germany and played 1,200 times from 1960 to 1964. It was all I needed to know because my personal top three influential artists are Stevie Wonder, The Beatles, and A Tribe Called Quest.

In beat-making, I’ve been way past my 10,000 hours years ago. But I don’t have 10,000 hours as a songwriter, and I didn’t realize that until I was asked that question in the interview last week.

It made me excited. I haven’t had to try and master a new craft in a while. I do learn new things all the time, and I love learning, but that is different than trying to master a specific skill set. The thought of me mastering songwriting and storytelling is very dope to me.

Now, I get to take all those methods I used to develop artist and apply them to myself. I’m on about song number 20, trying to get to song number 50. As a songwriter, I’m nowhere close to 10,000 hours, but just like beat making, I’m committed to the process and journey I’m starting as a songwriter and storyteller.

Monstalung

If you appreciate BBG's work, please support us with a contribution of whatever you can afford.

Support our stories