From Soil to Sovereignty: West Virginians Join the Black Farmers & Urban Gardeners Conference

By Black By God: The West Virginian

When you walk into the Black Farmers & Urban Gardeners (BUGs) National Conference, you don’t just enter a gathering — you step into a living ecosystem of Black agrarian brilliance, ancestral pride, and community action.

From October 3–5, 2025, at Wayne State University in Detroit — a campus rooted in the city’s Black history and located on Waawiyaataanong, the ancestral homeland of the Three Fires Confederacy — Detroit became fertile ground for growers, educators, chefs, and food-justice leaders from across the country.

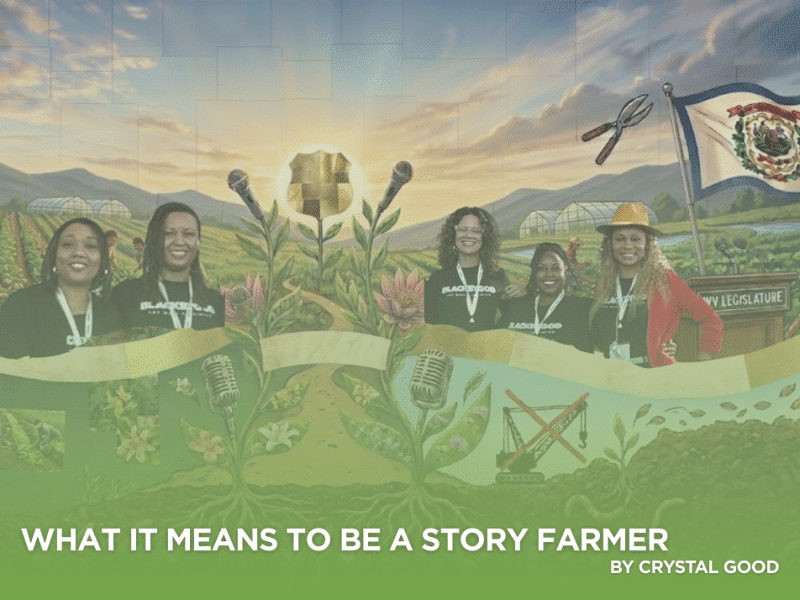

As West Virginians, our journey to BUGs carried particular weight, representing BLACK BY GOD: The West Virginian, where our AgriCULTURE content continues to grow — documenting how Black Appalachians reconnect with the land and reimagine food systems for the future, we traveled as a small mountain delegation — farmers, students, and organizers — who know what it means to wrestle with land: its beauty, its exploitation, and its promise.

- Chamear Davis, Mear Mae’s Meadow Founding Member; Black Girls Grow Founding Member

- Mavery Davis, Director of Lending, New Economy Works, WV

- Felicia Pannell, Unity Sisters Farm Owner; Black Girls Grow Founding Member

- Brian Mitchell, MSW Therapist, Inspiring Youth Coordinator – Keep Your Faith Corporation

- Octavia Cordon, Co-Founder/Worker-Owner of Phat Daddy’s on Da Tracks

- Cameron Rishworth, Graduate Researcher at the Center for Resilient Communities, WVU

- Heaven Smith, Undergraduate Research Assistant at the Center for Resilient Communities, WVU

- Linesha Frith, Keep Your Faith Corporation

- Dural Miller, Keep Your Faith Corporation/ Founder/CEO HARVEST Food Production and Distribution, Inc.

- Kea Miller, Keep Your Faith Corporation

- Crystal Good, Founder and Publisher of Black By God

Over three days, we participated in workshops on seed sovereignty, soil health, youth-led food justice, land access, and even farming as mental-health care. Between sessions, we visited the Detroit People’s Food Co-op — a Black-led, community-owned grocery emphasizing fresh, local food and democratic ownership.

“It’s one thing to study cooperation, but it’s another to live it,” said Mavery Davis of New Economy Works West Virginia, reflecting the co-op’s ethos of cooperative economics.

We toured community gardens that turned vacant lots into classrooms and sanctuaries — places where food was not just grown but taught, healed, and shared.

Revolutionary Acts of Growing Food

The opening keynote speaker was Tephirah Rushdan, Detroit’s first Director of Urban Agriculture and co-founder of the Detroit Black Farmer Land Fund. She began by naming the ground beneath our feet:

“We are in the place where the river bends. Before it was Detroit, it was a gathering place — a place of trade, of sustenance, of connection.”

Rushdan traced the city’s lineage from Indigenous river-farming and French ribbon farms through the Great Migration and redlining to its current moment of rebirth.

“Our city today stands about thirty percent open land… We’re turning that land into gardens and farms — places of self-determination.”

And she offered a truth that anchored the weekend:

“Never underestimate the revolutionary act of growing food. When we own the means of production, we free ourselves from systems that were never made for us.”

Ancestral Literacy and the Path to Sovereignty

Kentucky farmer and scholar Jim Embry, co-leading with Jennifer Baily, hosted one of the conference’s most powerful workshops, “Decolonization, Sustainable Agriculture, and Community Transformation.” They drew on the legacy of Carter G. Woodson, urging what Embry called “ancestral literacy” — remembering that knowledge of the land is knowledge of self.

This search for ancestral literacy hit home. In Detroit, we were struck by Elder Tariq Oduno’s powerful quote: “There is no culture without agriculture.” While this applies to any people, it holds a specific, painful weight for Black Americans. Post-slavery, agriculture became tainted by the trauma of forced labor, and for generations, we understandably ran from that connection to the land.

What we witnessed at the BUGs conference, and felt deeply in Embry’s workshop, was a collective determination to reverse that flight. This movement is a conscious re-establishment of our land connection. It’s more than just a collection of farms and gardens—it’s about building a Black sovereign food network, piece by piece.

“Soil is more valuable than gold.” — Jim Embry

The workshop explored how centuries of colonial systems fractured relationships with the Earth and marginalized Black, Indigenous, and women’s voices in agriculture, and Carver’s lesser-known research in fungi and plant communication became a metaphor for resilience.

Embry’s reflections found resonance in the work of Shayla Hunter-Lawson and Michael Hunter-Lawson of The IndiGo House, whose Kentucky farm merges art, ecology, and restoration — showing that farming itself can be an act of creative liberation.

From Detroit to Appalachia

Both Detroit and Appalachia understand extraction — of labor, minerals, and dreams — and what it means to rebuild from what’s left. Rushdan’s challenge rang familiar:

“Reducing the harm that conventional agriculture has brought to our planet is going to take more people growing food, owning the means of production, and teaching their babies the skills to live freely.”

For our Appalachian delegation, those lessons took root.

“Farming is growing food, but it’s also science, survival, and liberation,” said Cameron, a student at West Virginia University.

“Seeing 500 Black people from across the U.S. sharing joy and knowledge — that’s what freedom looks like.”

And for Heaven Smith, the weekend raised a lifelong question: Why don’t we teach agriculture to our youth sooner?

“In fifteen years of school, I never heard that growing food could be a career,” she said. “Dr. Monica M. White reminds us that freedom begins with community — and community begins with food.”

“This trip was about connecting our work in West Virginia to a national movement,” said Chamear Davis, founding member of Mear Mae’s Meadow. “We’re taking the seeds of sovereignty we gathered in Detroit and planting them directly in our Appalachian soil.”

Seeds of Change

BUGs was founded in 2010 by Suzanne Babb, Lorrie Clevenger, Regina Ginyard, and Karen Washington. BUGs has grown into a living network where land, culture, and community converge.

Back home in West Virginia, Heaven’s question lingers. The soil tells similar stories — of extraction and resilience, of dispossession and reclamation. Whether it’s coal dust or topsoil, we know what it means to fight for our land and the right to feed ourselves.

“Nobody in West Virginia should be hungry,” said Jason Tartt, a West Virginia forest farmer. “We have too much land — we have the capacity to grow enough food for our people.”

The 2026 BUGs Conference will be held in New Orleans. If you’ve ever thought about AgriCULTURE, about community, about change — get on the bus with us next year. Sign up for the BBG Agriculture Newsletter for updates and travel details.

Because from soil to sovereignty — that’s not just Detroit’s story.

It’s America’s Black agrarian revolution.

It’s West Virginia’s, too.

If you appreciate BBG's work, please support us with a contribution of whatever you can afford.

Support our stories