How Hip Hop Found Me in the hollow – My first newsletter for 100 Days in Appalachia

By: Monstalung

This article was originally published by 100 Days in Appalachia, a nonprofit, collaborative newsroom telling the complex stories of the region that deserve to be heard. Sign up for their weekly newsletter here.

This is part of 100 Days in Appalachia‘s Creators & Innovators Newsletters.

Hello,

Monstalung here. I’m glad to be your Creators & Innovators host for August.

This week, I want to tell you a little about how I got here. In 1979, my family moved to Log Town Hollow in Ansted, West Virginia, where my father’s roots ran deep. Before that, we – my brother Gandhi, sometimes my sister Sherie, and my mother, Brucella – moved around from place to place quite a bit, supporting my father’s pursuit of opportunities to perform his artistic talents as both a poet and playwright.

After the Gauley Mountain Coal Company closed in 1951, Dad’s family moved north. There, my father became a leading fixture within Cleveland, Ohio’s Black Arts Movement in the ‘60s and early ‘70s. As a child, I played conga drums for my father during some of his poetry readings and acted in all of his theater productions.

We lived in the West 25th Street projects, near an area called “The Flats.” It’s an upscale area now, with nice restaurants and clubs, but it wasn’t like that at that time. There was poverty, crime and dealing with gangs and bullies on daily encounters.

West 25th Street was also a quick walk to downtown Cleveland, and I went downtown a lot to escape the horrible environment of the projects. Being a young creative person, the downtown area made it easier for me to dream.

Both Sarah, my maternal grandmother, and Rose, my paternal grandmother, lived on East 88th Street, the street where my parents met, started dating and got married. Like a lot of 1970s Black families living in the inner city, grandmothers would take care of the children while the parents worked.

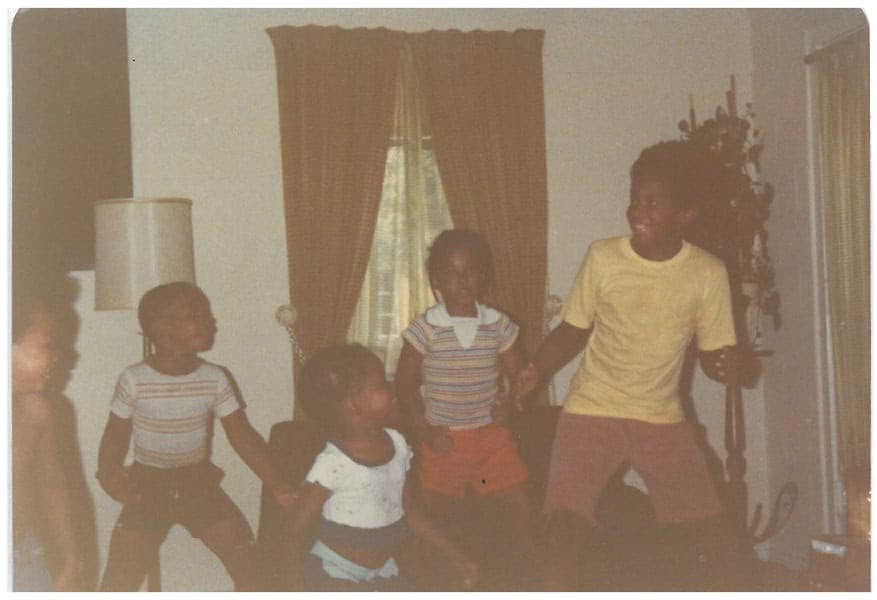

When I stayed with Grandma Sarah my cousins and I had a lot of fun together learning Jackson 5 routines and recreating Bruce Lee movies – all under my direction with me being the oldest and having some of my father’s artistic influence and talent. Grandma Sarah often took us to see double-feature martial arts movies. She enjoyed them, but I think she enjoyed watching us act out our favorite scenes more.

When I went to stay with my grandparents on East 88th Street I would hang out with my other cousins on that side of the family who were all into music and athletics. One of my Uncle Roger’s sons lived with Grandma Rose while the rest of them lived in New York. The New York cousins would occasionally visit Cleveland, and they would tell us about the new art form that included dancing, visual art, and something called “rapping.”

We didn’t know it at that time, but they were witnessing the beginning of hip-hop culture and shared it with us.

When my family settled in Ansted, West Virginia, my cousins from New York came to visit us sometimes; the ole “city cousins visiting the cousins in the country” was a way of keeping children from getting in trouble in the city during the summer. So, there was an exchange of cultures taking place. As my New York cousins continued my hip-hop lessons in Ansted, we got more details: about graffiti, about breakdancing, about freestyle rapping.

Our days also included pitch-up and tackle football next to the creek in our yard. We played basketball at the elementary school outside courts; with an 8-foot high basketball rim, we could all dunk the basketball on those courts. Freestyle rapping at the pavilion park baseball fields, we used our hands on the wooden benches to create drum beats as we freestyled.

My cousin David from New York had amazing graffiti art that he had drawn in his notebook along with raps. He was also the best athlete out of all of us. Slightly older than we were, he was our leader, and a good one – compassionate and supportive.

I hadn’t had anyone like that in Cleveland. Instead, I dealt with a lot of bullies in those projects. David was one of the first males in my age range who seemed like they really cared about my well-being, and he mentored me.

He also gave me my first mixtape. It was by DJ Red Alert, and that tape changed my life. Until I got that tape, I just heard a hip-hop song every once in a while. With that tape, though, I had 60 minutes of an up-and-coming New York hip-hop artist and a blueprint for the culture of hip-hop.

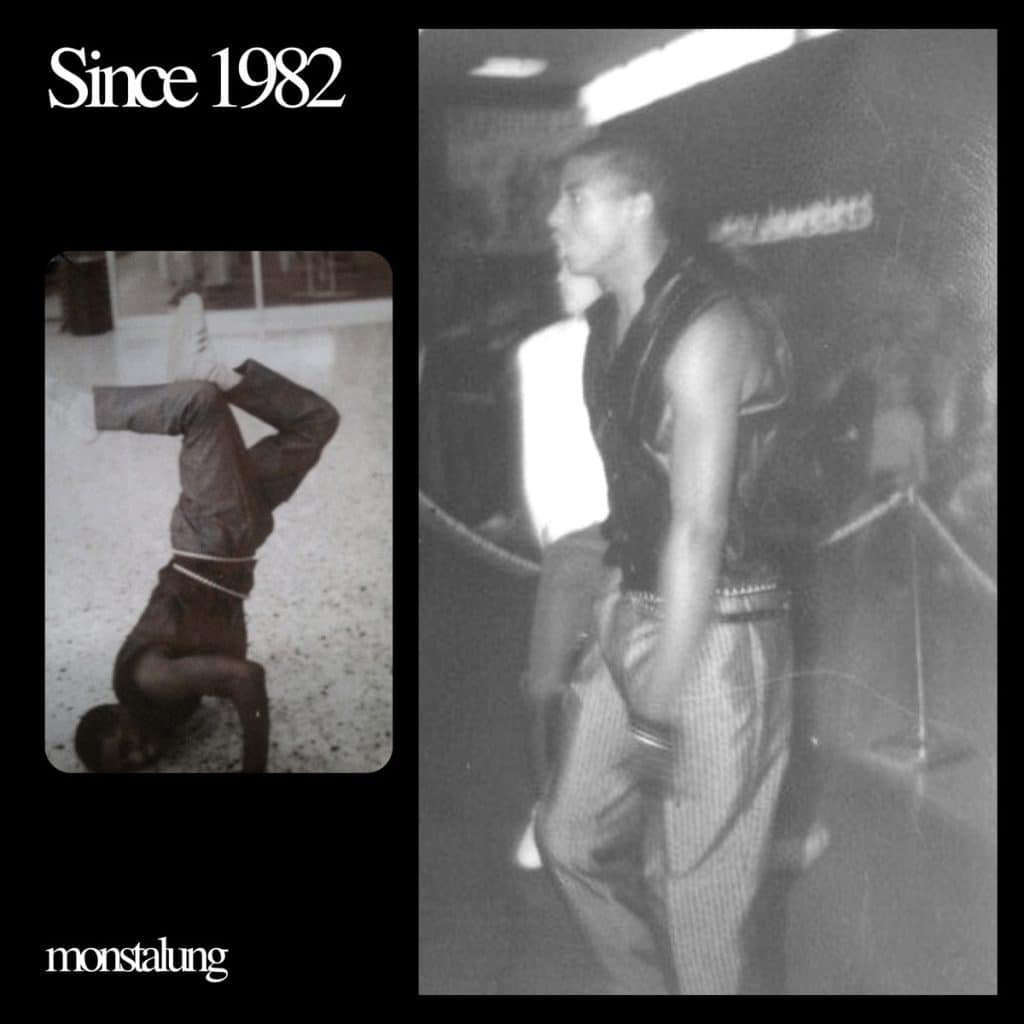

I’m not sure how much of my love for hip-hop culture would have happened had it not been for my cousins in New York. I was already into music and was a dancer, but once introduced to hip-hop it was love at first sight, and it’s been that way ever since.

In 1984 the movie “Beat Street” was released, and for us non-New Yorkers that movie gave us instructions about the “culture” of hip hop and the four elements of it: Graffiti, Breakdancing, DJing, and MCing. I identified and connected with the movie character Lee Kirkland, a breakdancer and younger sibling to the main character, Kenny Kirkland. Kenny was a popular DJ, but it was Lee’s presence and aura that drew me in and had an influence on me. I would see the same aura with Run from the group RUN-DMC, and also in LL Cool J.

I officially became a B-Boy (break dancer) after seeing that movie. I formed a breakdancing crew in Morgantown, West Virginia called the Robotic Atomic Footshockers. We rehearsed and did our routines at local high school dances, arcades, and malls, and even started getting booked for paid shows. Later in college, I transitioned into making beats, DJing, and rapping.

A few years after giving me that mixtape, my cousin David would be shot by a Cleveland police officer, which resulted in him being paralyzed from the waist down for the rest of his life. The officer thought he had a gun, but he only had a soda in his hands.

David passed away some years ago, but I’m sure he is proud of me because he loved hip-hop and taught it to me. Now I do the same, spreading my love for hip-hop, art, and culture in the hills of West Virginia.

– Monstalung

If you appreciate BBG's work, please support us with a contribution of whatever you can afford.

Support our stories