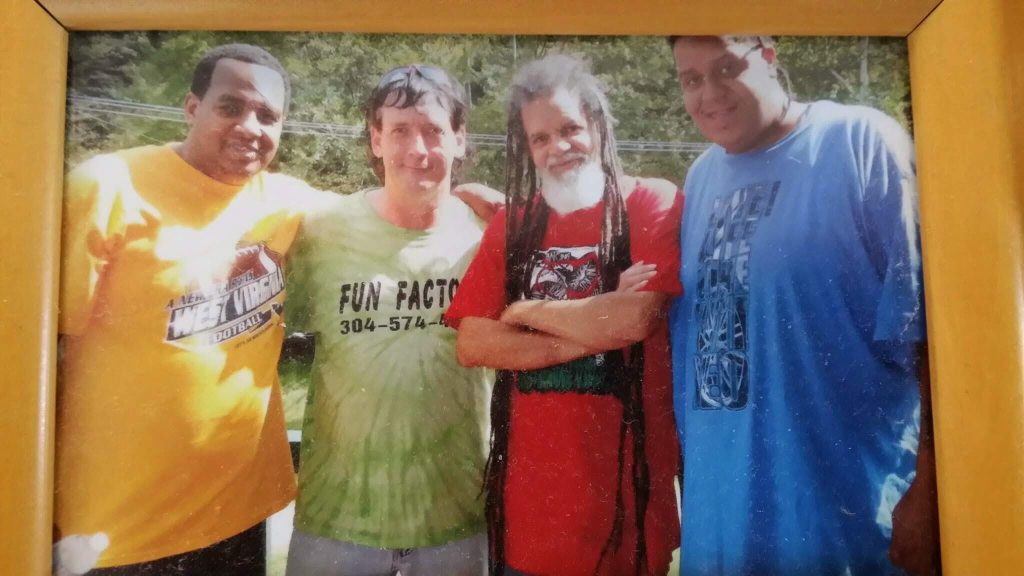

My brother James, not by blood, but by love

By: Monstalung

This article was originally published by 100 Days in Appalachia, a nonprofit, collaborative newsroom telling the complex stories of the region that deserve to be heard. Sign up for their weekly newsletter here.

This is part of 100 Days in Appalachia‘s Creators & Innovators Newsletters.

Hello, Monstalung here.

James was a white boy who lived across the road from our trailer on Log Town Road, in Ansted, West Virginia. My father, Norman Jordan, built an unshakable, loving bond with him and his family. I distinctly remember the first time my father introduced me, my brother, and James to one of his friends as his sons. We didn’t question it; in fact, we embraced it, and from there on out, I introduced James as my brother too.

My father and James had a special relationship. I used to see them walking and talking by themselves all the time, in a way that said to me “don’t interrupt them; they were talking about something important.” Again, they had an incredible bond.

One of James’ older brothers, Marvin, and I were the same age. We both loved to play pitch up and tackle football in our yard and basketball down on the dirt basketball court at the Skaggs family home. Marvin was a good athlete.

James’ other older brother, Ritchie, gave me my first stack of comic books. I’m talking about at least 40 comic books, and he said “when you’re done come back and get more.” Talk about a community feeding a young creative person.

My younger brother, Gandhi, and James were around the same age, and they were friends who played together all the time.

In my 9th grade year, my family moved to Morgantown as my father attended West Virginia University where he received his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in Theatre. Two years later, he earned a Master of Arts in African American Studies from the Ohio State University.

I was leaving for college by the time he graduated from WVU and my family moved back to Ansted. A few years later my brother Gandhi went off to prep school on a scholarship to play basketball for the illustrious Oak Hill Academy, a two-time USA Today National High School Champion. This meant there was no one left at home to help Dad with chores, as we had done before. Living in a West Virginia hollow requires physical work to maintain a property, and though my youngest brother Lionel was still around, he was too young to help.

Our parents were not getting any younger, though, so I worried. I would ask my parents how they were getting by. They would always say the same thing: that James or his other brother David had taken care of any problems. I mean yard work, car problems, electrical, carpentry, plumbing – whatever the issue was.

When I was available and able to help, I did whatever David told me to do because I had no clue about those types of things, but by watching and helping David I learned a little. Case in point, once when I was home for Thanksgiving just a few years ago, David and I built a handrail from the driveway to the walkway for my mother who is nearing 80 years old now. David and I went to Lowes to get materials to build the handrail. David knew exactly what we needed, and all the employees at Lowes knew him.

Under David’s direction, we built a very good handrail for my mother. I am thankful to David for that. That’s how we live in the hollow, despite our cultural differences and beliefs, which are significant. We still help and take care of one another.

I vividly remember my wife having a difficult time understanding our bond with folks who were so different from our family during her first visit to Log Town Hollow. My wife, Constinia, was born and raised in South Central Los Angeles, California, and had recently graduated from Howard University in Washington, DC. On our way to my parent’s trailer, I stopped at the town gas station that also rented videos. I went in to pick out a video and pay for gas while she waited in the car.

Shortly after, a truck pulls up with a man wearing a Confederate flag t-shirt with an image of Elmer Fudd garnishing two rifles on it (from the Bugs Bunny cartoon) with the text “Everything is Gonna be all WHITE.” My wife was scared, and quickly she locked the car doors, while frantically looking for me because she was concerned for my safety.

As I walked out of the gas station, I heard a loud voice scream “Eric!” It was the guy in the Elmer Fudd shirt! He was someone I knew living in Ansted when I was younger. We greeted each other, smiled and hugged one another, talked and caught up on one another’s lives.

I glanced over at my wife and noticed that she was confused and taken aback. After I finished pumping the gas, I knocked on the window for her to unlock the car door. She was silent, which is usually not a good thing for me.

She said, “I am at a loss for words,” as she continued to look at me in bewilderment and slight disgust. She then aggressively asked me, “Did you see his shirt?” I replied, “That’s just how it is down here, we coexist.” My wife loves to tell this story to her family and friends when they ask why she loves West Virginia and its people, despite our differences.

Another story my wife loves to tell centers around a conversation with my brother, James, at a Thanksgiving dinner in Ansted. Somehow, the topic of politics came up, and James decided to share with her his disdain for then-President Barack Obama. He was adamant about how he was bad for the country.

My wife was so mad, sitting in a chair right below a picture of the Obama family on the wall behind her, but my father laughed it off and casually changed the subject. My wife calmed down, and accepted the shift in conversation, as my father began to tell a funny story about when all his children, including James, were growing up. We had a great Thanksgiving dinner; we coexisted in the spirit of love and family.

The first song I wrote for my album that came out this past June is called “Coexist.” The song specifically talks about living in Logtown Hollow, and Appalachia, during the late 1970s. The name of my album is “An Appalachian Hip Hop Story Pt.1,” and one of the reasons I named it is to show that Appalachians have many unique and untold stories to tell that look different from what some may think defines Appalachian.

When my father passed in 2015, James would tell me all the time, “Don’t worry, bro, I’m gonna’ take care of Mom…don’t worry bro.” He wanted me, and my siblings to know, that he was there for my mother, as none of us lived close to Ansted.

He kept his word to us until his untimely death. My brother, James, passed away in 2019, and now his brother (my other brother), David, continues to look after my mother. My brothers, James and David, are indeed family not by blood, but by love.

Sincerely,

Monstalung

If you appreciate BBG's work, please support us with a contribution of whatever you can afford.

Support our stories