Morrisey wants $10 million for AI flood warning. The bill to allow it would also remove a resiliency fund’s spending requirements around poor communities & payments to homeowners.

If passed, SB 390 would loosen restrictions on how the West Virginia Flood Resiliency Trust Fund — which has never been funded — can spend its money.

CHARLESTON, WV — On Thursday, West Virginia lawmakers took steps toward modernizing the state’s flood warning system, by passing Senate Bill 390 out of committee. The bill comes at Gov. Patrick Morrisey’s request, after he put $10 million for an artificial intelligence-driven advanced warning flood system in his proposed budget. If passed, SB 390 would loosen restrictions on how the West Virginia Flood Resiliency Trust Fund —which has never been funded — can spend its money.

As state law is currently written, the fund is required to spend specific percentages of funding on helping low-income communities, nature-based solutions, floodplain restoration and paying people for their homes and relocation.

SB 390 would create a more tech-heavy resiliency plan to prepare in advance for disasters. Central to the plan is a revolutionary AI-based approach, explained to lawmakers in committee by Matthew Blackwood, the acting director of the West Virginia Emergency Management Division.

During his testimony, Blackwood outlined a 36-month pilot program that would use AI modeling to predict floods. Unlike traditional methods, this system would “learn” from real-time data points including soil moisture, previous rainfall and snowmelt to provide early warnings. The technology would allow up to six hours of additional warning time.

We’ll bring the best from BBG right to your inbox. You can easily unsubscribe at any time.

Sign Up for our Newsletters!

If SB 390 is passed and Morrisey’s request is approved, the pilot program would launch in seven key river basins, before expanding across the entire state. The proposed technology is modeled after successful systems used in Raleigh, North Carolina, and it aims to provide highly specific data for early warnings ahead of floods.

Del. Jack Woodrum, R-Summers, noted that the gauges in the Greenbrier River watershed in his county only work sometimes. He asked if the proposed system would rely upon information from faulty gauges, supplement them or replace them.

“I don’t think there’s a simple answer,” Blackwood said. “Except that what we will be doing in each watershed when we roll this out, we’re going to ensure that the SENTRY — this program we’re developing — that it will ingest any available data that’s there now.”

Woodrum shared appreciation for the work Blackwood and other state officials are doing.

“I also met with your office and looked at the modeling and know how many close calls the state of West Virginia has had that were near misses when you had major [flood] systems getting ready to collide over our state,” Woodrum said. “So, I appreciate what you’re doing and certainly believe it will save lives.”

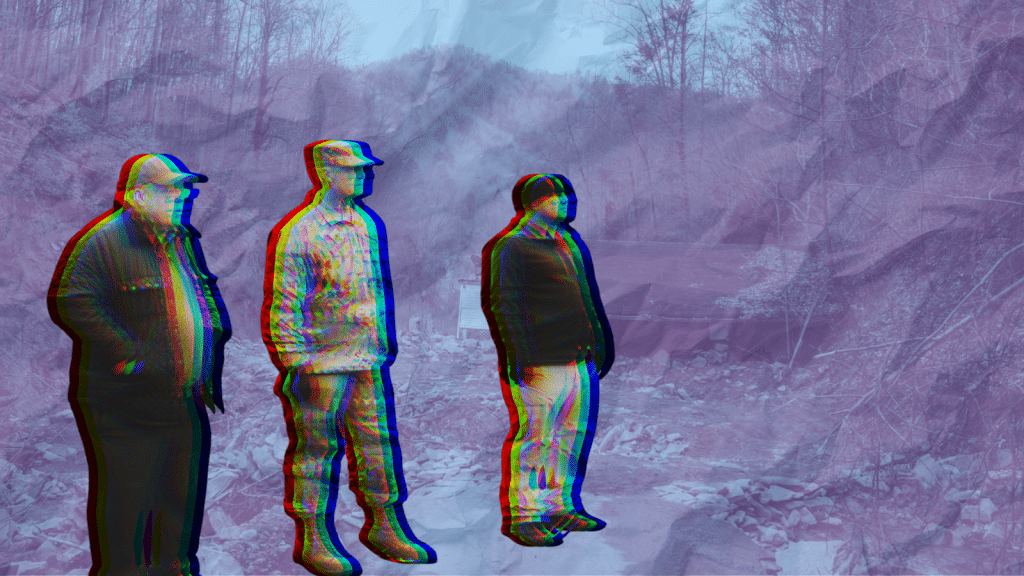

Lives are absolutely on the line when it comes to flooding in West Virginia.

About one year ago, the southern coalfields experienced record-breaking floods, as West Virginia Watch reported. Stores were destroyed. Bridges collapsed, and roads washed out. Homes were filled with flood mud: a combination of water, soil, chemicals, sewage and other health hazards. Several people died. If that wasn’t enough, many West Virginians were forced to clean up with brown tap water, due to the ongoing infrastructure crisis in the state’s southern coalfields.

For the residents of West Virginia who have spent generations cleaning flood mud out of their living rooms, the stakes could not be higher. The shift from “recovery to prevention” sounds good in a press release. But for those in the southern districts, the success of Senate Bill 390 will be measured not in the accuracy of an algorithm, but in the dryness of their basements.

The government’s previous inaction on flood resiliency has left many West Virginians skeptical that new bills will actually make a difference. Even though West Virginia created the Flood Resiliency Trust Fund back in 2023, elected officials have kept it unfunded with a $0 balance, according to Mountain State Spotlight. Even if the Legislature fills the fund, SB 390 would change the way money is spent.

Right now, if the Flood Resiliency Trust Fund had money, it would have to spend at least half of the funding it disburses on helping low-income areas and low-income households. SB 390 strikes the section of law that requires that. It replaces it with language saying that the fund just needs to “prioritize benefiting low-income geographic areas or areas with a history of frequent or significant flooding events.”

Current state law also requires the fund to spend at least half of the funding it disburses on nature-based solutions. And no less than an eighth of the money it disburses must be spent on these three things combined: buying up housing, giving residents relocation assistance and doing floodplain restoration activities on the properties it has purchased.

SB 390 would remove several sentences from current law and replace them with language saying disbursements from the fund “may be used” for those initiatives.

This change could have serious implications, particularly for Black West Virginians. When it comes to non-coastal flooding, Black Americans are 10 percent more likely to live in areas with the highest projected damages, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Kanawha and McDowell are among the top five Blackest counties in West Virginia, and they also sit in the top three for highest cumulative flood risk index. That statistic estimates where flooding is most likely and where it would do the most harm.

While a long-term AI pilot program may help predict floods earlier, many community members say it can’t fully replace boots on the ground, immediate investment in communities that are already at risk or financial assistance to help people recover after floods.

“After being flooded in 2003, I’ve come to realize my life will never be the same,” said Boone County resident Mariah Gunnoe. “No one can pick up the cost of this without help. It takes everything, leaving nothing untouched.”

SB 390 will likely be up for a Floor vote on Wednesday. If passed into law, it could lead to profound technological upgrades for West Virginia’s emergency infrastructure. But, when rural communities hear about AI models and 36-month pilot programs, many worry this is another plan that sounds good on paper, but will leave them mopping mud off their floors.

If you appreciate BBG's work, please support us with a contribution of whatever you can afford.

Support our stories