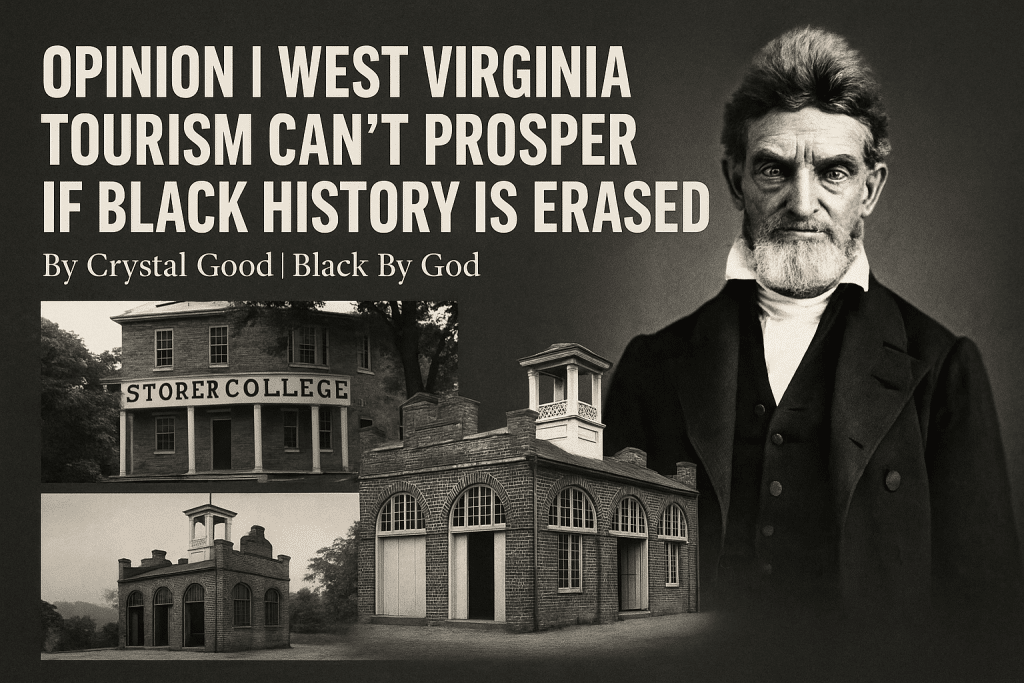

Opinion | West Virginia Tourism Can’t Prosper If Black History Is Erased

By Crystal Good | Black By God

Editor’s Note (Updated November 4, 2025)

This opinion essay was originally published on September 16, 2025. It reflected concerns about the reported removal of slavery-related signage and exhibits from Harpers Ferry National Historical Park.

Current status: Despite those discussions, the signs and the full historical context of Harpers Ferry — including its history of slavery, abolition, and John Brown’s raid — remain intact and are still part of the park’s educational materials.

The piece also described the “Lovett Hotel” as “a Black-owned haven for travelers barred from white-only establishments.” That was inaccurate. The establishment in question, the Hill Top House, was founded by Tom and Lavinia Lovett, a Black couple whose entrepreneurial success in Harpers Ferry was remarkable. However, the hotel operated as a whites-only establishment during their 35 years of ownership.

For a fuller account, see our feature, “Black-Owned, White-Only: New Book Profiles the Hill Top House Founders,” about Lynn Pechuekonis’s new book Among the Mountains: The Lovetts and Their Hill Top House.

The Trump administration has begun removing signs and exhibits about slavery from Harpers Ferry National Historical Park. According to National Parks Traveler, more than two dozen items have already been flagged and pulled after President Trump’s March 2025 directive to eliminate materials that “disparage Americans past or living.” Interior Secretary Doug Burgum ordered staff across the Park Service to review signage, while new postings invite visitors to report “questionable” exhibits. The Washington Post first broke the story, and ARTnews confirmed that one of the targeted displays was The Scourged Back (1863) — the iconic photograph of Peter, an enslaved man whose scarred back bore witness to slavery’s brutality.

The photo of formerly enslaved man Peter Gordon is known as “The Scourged Back” and shows his back heavily scarred from whippings. The photograph is attributed to two photographers, McPherson and Oliver, who were in the camp at the time. It became one of the best-known photographs of the Civil War and a powerful weapon for abolitionists. Ken Welsh/Design Pics/Universal Images Group via Getty Images from yahoo! news.

This is not just a bureaucratic adjustment. It is an act of erasure.

To understand what’s at stake, remember why Harpers Ferry is sacred. In October 1859, abolitionist John Brown led a daring raid on the federal arsenal there, hoping to arm enslaved people and spark a national uprising for freedom. The raid failed, and Brown was captured and hanged that December in nearby Charles Town — but his sacrifice electrified the abolitionist movement and pushed America closer to civil war and emancipation. Frederick Douglass called Harpers Ferry “consecrated ground.” W.E.B. Du Bois later wrote:

“John Brown was right … ‘Slavery is wrong,’ he said,—‘kill it.’ Destroy it — uproot it, stem, blossom, and branch.”

When those signs come down, so does the truth of freedom’s struggle. Harpers Ferry is not just John Brown’s story — it is the story of enslaved people who longed for liberty, the free Black communities who built schools and businesses here, and the abolitionists who risked everything to end slavery. Erasing that history dishonors all of them.

Harpers Ferry has long been a cornerstone of Black history in America. Storer College, founded in 1867, educated generations of Black teachers and leaders. In 1906, W.E.B. Du Bois convened the Niagara Movement on its campus, planting the seeds of the NAACP. The Lovett Hotel, once a Black-owned haven for travelers barred from white-only establishments, is now being rebuilt — a reminder of Black entrepreneurship and resilience. When interpretive signs vanish, this larger legacy — of Black education, activism, and business — also disappears.

The economics of this erasure are just as real. In 2023 alone, 427,317 people visited Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, spending $23.8 million in nearby communities. That spending supported 319 local jobs and generated a $37.7 million boost to the local economy (National Park Service, 2024). Across the state, tourism brought in more than $6.3 billion in visitor spending, generated nearly $900 million in tax revenue, and supported almost 60,000 jobs in 2023 (West Virginia Department of Tourism, 2024). That’s not just numbers on a chart — that’s waiters, innkeepers, shop owners, tour guides, and families depending on those dollars.

And let’s not forget: Harpers Ferry sits just over an hour from Washington, D.C., home to some of the nation’s wealthiest Black ZIP codes, where average household income tops $300,000. People with means should be coming here — yet when we erase the story of slavery and abolition, we make West Virginia seem unwelcoming or even “scary.” The truth is, it isn’t. Black By God exists to help people see that. We are no different than the rest of this country in its crises, but our stories — of struggle and of triumph — deserve to be told, and told honestly.

Here’s a little fun fact: Dick Gregory, the legendary comedian and civil rights activist, made Harpers Ferry a site of pilgrimage.

As he once said:

“Every year on my birthday October 12th I go to Harper’s Ferry, and every 2nd of December I go to Charles Town, West Virginia and hug the tree next to where John Brown was hung. I hug the tree for the white man who gave up his life for a black man. John Brown took his two sons with him. Then the whole world changed thanks to John Brown. I came here to say thank you.” (Legacies of Slavery, 2022)

I used to leave notes for Gregory in Harpers Ferry because I knew he always came for his birthday. It was my way of joining his ritual, my way of remembering.

That is why Black By God is creating our Touring & Travel issue — a modern-day Green Book for West Virginia. If the Park Service won’t tell the full story, then we will. The guide will map the places where Black history lives — Harpers Ferry, Huntington’s Carter G. Woodson Memorial, Malden’s African Zion Baptist Church, the coal camps where Black miners built communities, and the businesses, new and old, that keep this heritage alive. It will show travelers where to feel safe, where to belong, and where to invest their dollars in communities that deserve to share in tourism’s prosperity.

West Virginia’s Black history is not a burden — it’s an asset. From Harpers Ferry to Huntington, from Malden to the southern coalfields, this state holds stories of abolition, education, faith, labor, music, science, and resilience that shaped not only West Virginia but the entire nation. It is the history of the African Zion Baptist Church in Malden, the state’s first Black church. Of Black miners who carried communities on their backs and fueled West Virginia’s economy. Bill Withers, who sang the world into joy and comfort from Slab Fork. Katherine Johnson, the NASA mathematician from White Sulphur Springs whose calculations carried astronauts safely to space. And yes, even of politics, with Black West Virginians holding seats in the legislature as early as Reconstruction — proof that Black voices have always been part of shaping this state’s future.

This legacy is a resource for tourism, for education, for pride. It is something to be celebrated and made known, not hidden away. When we erase it, we don’t just lose history — we squander one of our greatest treasures.

When the signs come down, we won’t just lose revenue — we are losing history.

And that is a dangerous thing.

Support the Black By God Touring & Travel Issue

Here’s how you can help:

- Donate to fund reporting, design, and printing.

- Distribute the issue in your community and beyond.

- Stand with us by sharing the work and believing in the BBG mission

If you appreciate BBG's work, please support us with a contribution of whatever you can afford.

Support our stories