“There’s a Farmer on the Flag”: New BBG Podcast Launches Conversations on Black Land and Agriculture in Appalachia

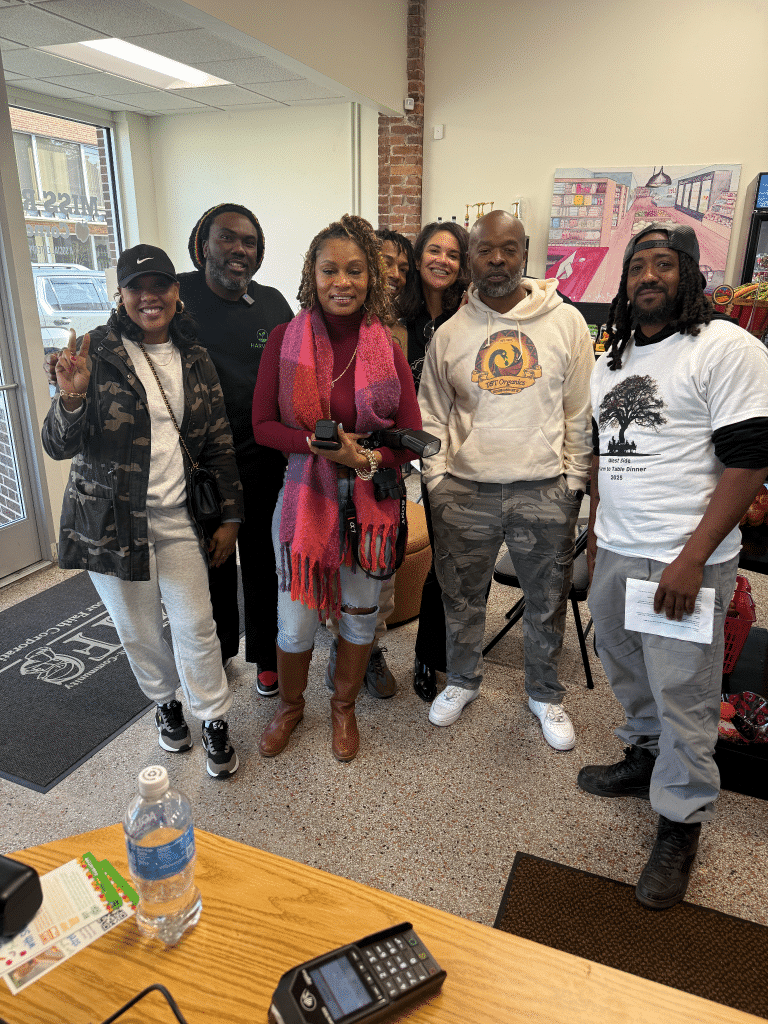

Traci Phillips, Dural Miller. Leeshia Lee, Jason Tartt, Mavery Davis, Jonah Dyer, Crystal Good. The inaugural episode features farmers Jason Tartt and Dural Miller, hosted by Mavery Davi,s discussing cooperative economics, food sovereignty, and reclaiming ancestral land.

Black By God: The West Virginian is launching a new podcast series titled “There’s a Farmer on the Flag: Black Land, Black Hands, Black Futures,” featuring intimate conversations with Black farmers, food producers, and land stewards across West Virginia.

The series takes its name from West Virginia’s state flag, adopted in 1863, which features a farmer and a miner, though history often obscures the contribution of Black folks, women, and many other hands that have actually been working the land and mining the coal in West Virginia.

Farmer on The Flag Vision

“There’s a Farmer on the Flag” centers on three core principles: Food is revolution. Land is freedom. Agriculture is culture.

The podcast documents and amplifies the work of Black agricultural leaders across West Virginia, exploring how communities are reclaiming land, building food sovereignty, and creating generational wealth through farming.

Future episodes will feature Black farmers, food scientists, herbalists, land trust organizers, and next-generation leaders working to transform Appalachia’s food systems. The series is available on Black By God’s website and YouTube channel, with shorter clips shared across social media platforms.

Subscribe to the BBG AgriCULTURE Newsletter for the official launch

Episode One: Building Food Sovereignty from Charleston to McDowell County

The inaugural episode, filmed inside Miss Ruby’s Corner Market on Charleston’s West Side, brought together Jason Tartt, co-founder of TNT Organics and McDowell County Farms, and Dural Miller, founder of Keep Your Faith Corporation and Miss Ruby’s Corner Market.

Hosted by Mavery Davis, the hour-long conversation explored cooperative economics, urban and rural farming models, beekeeping as economic opportunity and therapy, the need for processing infrastructure, and lessons from Detroit’s Black urban farming movement.

From Crisis to Calling

Jason Tartt’s agricultural journey began when he returned to McDowell County to care for his sick mother and discovered his community facing poverty, addiction, and life in a food desert.

“I learned the term ‘food desert’ and realized that my own neighbors were living inside one,” Tartt recalled. “Instead of turning away, I asked myself: ‘If I don’t do it, who will?'”

That question led him to form TNT Organics and build a cooperative model addressing poverty, unemployment, and food insecurity simultaneously. His work now includes training programs, youth pipelines, and a 350-acre demonstration farm developing high-value mountain crops like maple syrup, honey, and berries.

Miss Ruby’s: More Than a Market

Dural Miller’s journey started with two garden plots meant to bring fresh food to Charleston’s West Side. What began as raised beds bloomed into Miss Ruby’s Corner Market—a community hub that’s part grocery store, part safe haven.

“People come here to breathe, to talk, to find comfort,” Miller explained. “One brother came in just needing someone to listen. The store wasn’t just about food—it was about presence.”

Named after Miller’s grandmother, the market embodies her teaching: treat people right, feed people, and keep faith.

Cooperative Economics as Cultural Continuity

A central theme was the cooperative model as a continuation of African and African American survival strategies.

“Co-ops aren’t just business models—they’re cultural continuations,” Tartt explained. “It’s how Black folks survived in this country from the beginning—collective economics. Pooling resources. Sharing risk. Sharing reward.”

The conversation also highlighted practical needs: processing infrastructure to bottle honey, can vegetables, and reduce food waste; youth education programs teaching the next generation; and the transformative power of land ownership.

“When we control our food, we control our destiny—economically and socially,” Tartt said.

Miller added, “If I don’t teach it, I can’t keep it alive. Teaching the next generation practical knowledge means they can build from the foundation, not start from zero.”

Subscribe to the BBG AgriCULTURE Newsletter for the official launch

If you appreciate BBG's work, please support us with a contribution of whatever you can afford.

Support our stories